- Red Cloud ›

- Plains Indian 1873-1876 Manikins

Plains Indian 1873-1876 Manikins

Red Cloud Links

Content Analysis of the Photograph: Plains Indian Manikins–History in Museums

After identifying the artifact–the stereograph taken in 1873 in theSmithsonian Castle by C. Seaver–we began our content analysis of the image. The manikin itself headed our first queries. Manikins used at the Smithsonian Institution at that time have been described as made of wax and "so poorly modeled that they were soon discarded." Although the Indian Chief appears to be the first manikin at the Smithsonian representing Plains Indians, it should be noted that this was not the first American Indian manikin produced. Charles W. Peale, a well known portrait painter, had a collection of Indian materials that he exhibited in Philadelphia in 1797 that included lay figures or "mammoth Indian figures" in appropriate dress.

The Manikin's Identification on the Print

The C. Seaver stereograph of the manikin was identified only as "Indian Chief" while the Jarvis stereograph of the manikin was identified as "115. Red Cloud." That this manikin can be positively identified as Red Cloud, or Mahpíya Lúta, the famous Oglala Teton Sioux warrior-statesman, is demonstrated here through ethnohistorical research. The identification was then verified through comparisons of the photographs using computer analysis of the images.

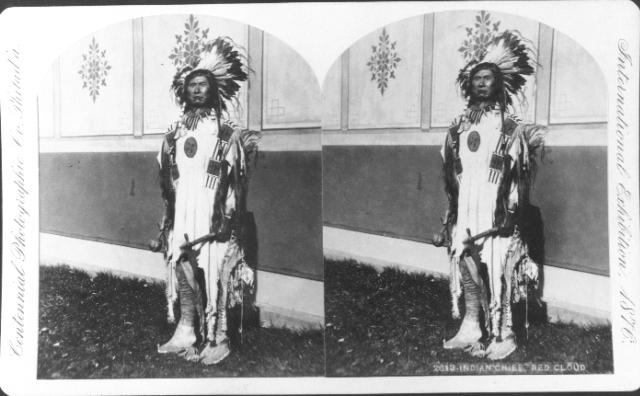

As shown in yet another stereograph, a manikin identified as Red Cloud was displayed at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, which opened May 10, 1876 (Figure 7). The manikin at the Centennial was one of dozens of life-size manikins created by Smithsonian personnel to display Native American clothing, weapons, and tools. The Red Cloud manikin was wearing many of the same items of clothing as the Indian Chief manikin of 1873. By 1876, stereographs of this manikin were being sold by the Centennial Photographic Company clearly identified as "2613. Indian Chief. Red Cloud." The Jarvis image probably was labeled "Red Cloud" following the identification from the Centennial photograph because of the similarity of the Indian figure and its clothing.

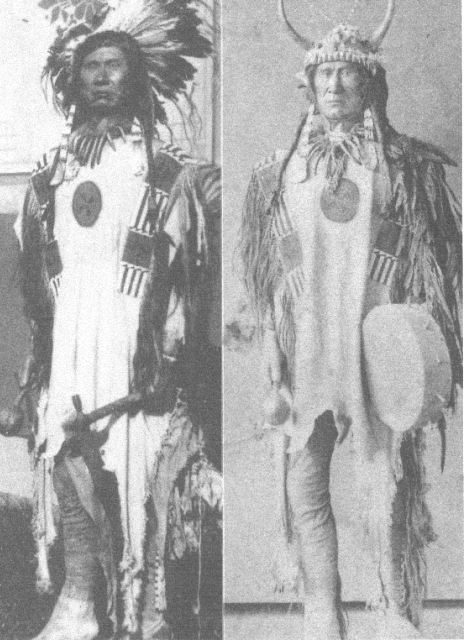

After carefully comparing photographs of the two manikins–the one exhibited in 1873 at the Smithsonian and the one exhibited in 1876 at the Centennial–we did not believe at first that they were the same figure or head. However, thanks to Jane Walsh, Smithsonian, and her computer scanning recreations, we are now convinced that the two manikins in the photos are the same and were modeled after a photo of Red Cloud made in May 1872.

The Red Cloud Manikin's Physical Features

Apparent subtle differences between the physical features of the 1873 and 1876 manikins in the photos (Figure 8) result from the fact that one was photographed in daylight outside the Centennial building in Philadelphia while the other was photographed inside the Smithsonian Castle. The angle of the camera was also different. The camera position for the 1873 image was more elevated than that of the 1876 photo. Notice that the position of the hand and the stance of the right leg are the same. The areas of closest parallel are the chin, neck, and nose. The wig also appears to be the same. The face of the 1876 figure looks much darker, which was one of the reasons it was initially believed to be a different manikin head. An article in The Evening Star (September 18, 1886) of Washington, D.C., made the following observation to describe the making of manikins by the Smithsonian: "When the series of Indian figures was prepared for the Centennial Exposition the heads were all taken from one mask.… The gentleman who arranged them did the best he could by painting the face differently, which gave them some variety." Red Cloud's face may be darker on the 1876 manikin because it, too, was painted.

In comparing the clothing of the manikins (Figure 8), both wear the same shirt, leggings, moccasins, and bear claw necklace. There are also differences: the 1873 manikin wears a horn headdress with feather trailer and holds a drum and drum beater or rattle, while the 1876 figure wears a warrior's feather bonnet and holds a pipe tomahawk and a wooden club or rattle.

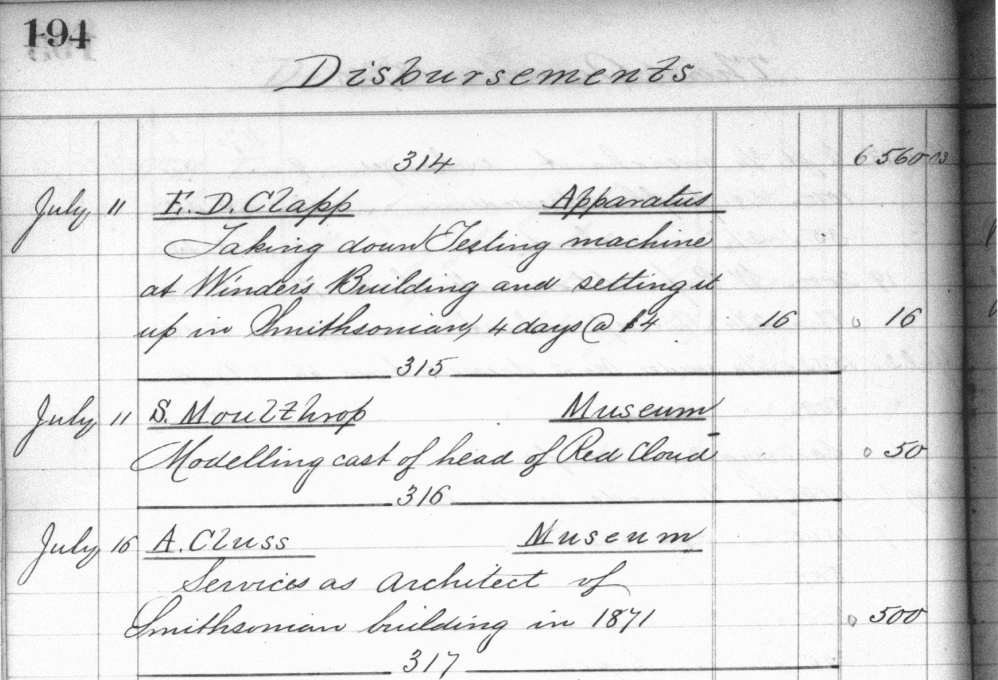

After this comparative analysis of the physical features was completed, further research in the Smithsonian Archives (Figure 9) discovered that a sculptor named Sidney Moulthrop had been paid $50 for "modeling cast of head of Red Cloud, July 11, 1872." Had we discovered this information earlier in the research some of the comparative analysis of the manikin and the photograph of Red Cloud would not have seemed so critical. However, it is always good to confirm a hypothesis, and our methodology of comparing the manikins may be useful to future researchers.

| ← Previous | ↑ Back to Red Cloud home ↑ | Next → |

[ TOP ]