- Red Cloud ›

- Manikin Clothing and Paraphernalia

Manikin Clothing and Paraphernalia

Red Cloud Links

Content Analysis of the Photographs–Clothing and Paraphernalia

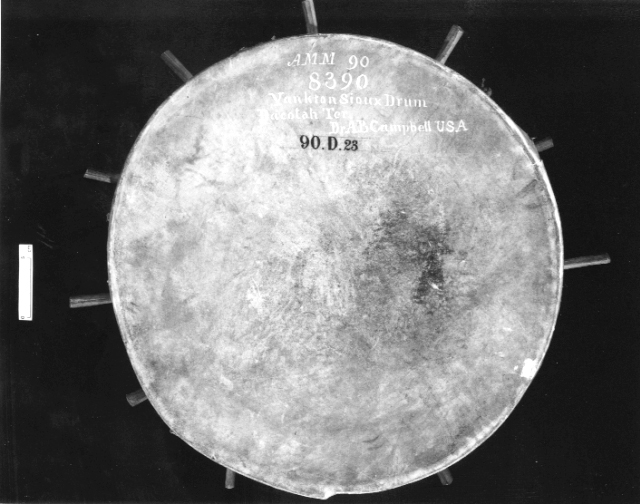

Because the drum held by the figure in the 1873 photograph had a prominent museum catalog number (Figure 11, white lettering appearing on front of drum), the research led to the Smithsonian Department of Anthropology's ethnological holdings. The purpose of searching for the individual pieces of clothing and other artifacts was to help narrow down the date when the manikin was made and first put on display. The Yankton Sioux drum, collected in 1868, was part of the Army Medical Museum Indian collection transferred to the Smithsonian in 1869. Knowing this allowed us to narrow the date that the manikin was made to after 1869 but before May 1873, when the photograph was copyrighted. The Arapaho moccasins (Figure 12) and Sioux earrings were also from the Army Medical Museum and transferred to the Smithsonian in 1869. The Sioux headdress (Figure 13) was collected by Lt. G.K. Warren much earlier, in 1855, so it was not helpful in narrowing down the date. However, the headdress originally had a feather trailer (Figure 14), as was first observed by Felicia Pickering, Smithsonian. The leggings were also part of the collection by Warren in 1855 and were, in 2002, displayed on a Sioux manikin at the Smithsonian's NMNH. The bear claw necklace could not be found in the collection. The 1873 manikin is also shown holding a drum beater or rattle, but this could not be found in the collection either.

The Shirt

| Smoke's shirt, front | Smoke's shirt, back |

|---|---|

|

|

One of the most interesting discoveries was the beautifully quilled and beaded skin shirt (Figure 15). To begin the search for the shirt worn by the manikin, we first used the summary of ethnological objects prepared in 1996 by the Repatriation Office in NMNH and found that there were 30 Plains Indians shirts in the Department of Anthropology's collection. After previewing the cataloged information we actually looked at only five shirts. We easily identified the one on the manikin. It was currently labeled “T-1120 War shirt, Sioux??” with no other provenance. A “T” (temporary) stands for an unidentified object in the collections. After a review of the catalog cards of the other Plains Indians shirts in the collection, catalog card number 1851 was found. The card stated that this shirt had not been located as of May 1998 but it gave detailed information about it from an accession letter. The card noted that the shirt was a gift to William O. Collins from Chief Smoke prior to Smoke's death in the autumn of 1864; in 1866 Collins donated it to the Smithsonian.

Chief Smoke, or Sóta [pronounced Shota], was an Oglala Sioux. He had a sister named Walks as She Thinks who married a Brule Sioux chief. They had a son, Red Cloud. Both parents died around 1825, leaving Red Cloud and his siblings to be raised by his mother's brother, Chief Smoke. Thus from an early time Red Cloud was associated with Smoke's family.

The information fit the shirt that had no provenance and that our manikin had worn. First, it was much larger than most of the Plains Indians shirts in the collection and thus owned by a very large individual, such as Lt. Col. Collins described about Chief Smoke in his accession letter (Smoke was said to weigh at least 250 lbs.). The shirt was decorated with well-executed seed beads, a V-shaped neck flap, and a large circular beaded disc attached to the center of the front and back, surrounded by small circular quilled discs. The designs and colors of this early beadwork example have a decidedly Cheyenne look, possibly the result of the tendency of Oglalas to marry Cheyenne women. The back of the shirt has more decorations than the front. According to the accession letter, the back also had a number of horsehair locks dyed yellow and blue along the margins of the beaded bands together with ermine, both winter white and summer brown. According to an analysis of the hairs on the skin, the shirt is made of two elk skins with the hair fringe preserved on the edge. The yellow and blue/green painted horsehair fringes represent horses captured in war and herald Chief Smoke's military accomplishments. The extensive decoration of this shirt, the presence of the neck flap (a symbolic remnant of a knife sheath worn at the throat–a symbol of a successful war chief), and the use of the colors yellow and blue indicate that the shirt belonged to an important chief.

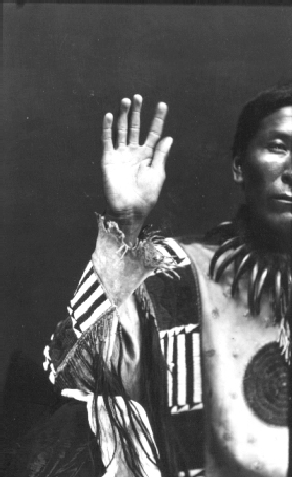

Through the years, Chief Smoke's shirt became something of a studio prop used by 19th century Smithsonian photographers and ethnologists for dressing up their Indian subjects or consultants. One such series is of Tichkematse, or Squint Eye, a Cheyenne Indian who worked for the Smithsonian between 1879 and 1881 (Figure 16). A series of 29 photographs show Squint Eye wearing Chief Smoke's shirt, demonstrating sign language gestures. Squint Eye was working with Frank Hamilton Cushing, an ethnologist with the Smithsonian Institution at the time, when these photographs by Thomas W. Smillie were made in 1879. Drawings made from these photographs were used to show types of hand positions of certain signs and were used on printed forms made by the Bureau of Ethnology for recording descriptions of gestures for the study of Plains Indian sign language.

While it is not known whose idea it was to dress Squint Eye in Chief Smoke's shirt, a long-haired wig, and a bear claw necklace, the purpose was obviously to make him look genuinely “Indian.” Other photographs of Squint Eye, taken at the same period, show him with short hair and wearing a business suit, his everyday attire during his employment at the Smithsonian.

The last photograph found that has a visiting Indian wearing Chief Smoke's shirt is one of John Grass (Figure 17). Taken by De Lancey Gill in 1912, it appeared as an illustration in Frances Densmore's 1918 study of Teton Sioux music. Grass is wearing a Euro-American cotton shirt under the buckskin shirt, as can be seen by the collar, so without a doubt donned Smoke's shirt for the photography session. By this date the origin of the shirt had lost its original identification as Chief Smoke's shirt. It had become, instead, associated with a famous Indian celebrity, Red Cloud, and that in itself may have led to its popularity.

Conclusion

Only through the clues provided by historical photographs was it possible to reassociate the shirt with its proper provenance and the feather trailers with the headdress, a valuable byproduct of the study of images that in themselves were equally undocumented. In addition, we positively identified the earliest Plains Indian manikin at the Smithsonian as the popular, well-known Chief Red Cloud and the shirt as belonging to his uncle, Chief Smoke. It is also clear that the use of these manikins from the 1870s to today is basically the same. That is, the tradition of showing native peoples in displays frozen in the ethnographic present of the late 19th century is itself frozen in the museum setting. The rewards of careful study of historical photographs go far beyond mere illustrations and demonstrate that images are in and of themselves primary documents capable of providing valuable information that may lead scholars in various unsuspected directions and end with surprising results.

| ← Previous | ↑ Back to Red Cloud home ↑ | Next → |

[ TOP ]