By Joanna Cohan Scherer

Conclusion

Without regard for the historical circumstances of their creation, pressure is now being brought to bear in many picture repositories to restrict access to a growing range of photographs.17 Questions are being asked by American Indians as to the intellectual ownership of many of these images and the ethics of viewing and publishing images that are considered by some today to be too sacred, too personal, or too sensitive. Some of these voices proclaim that if the subject of the photograph is a ceremony performed only for men or women, members of the other sex should not be allowed to view it, even in photographs; if it is of a relative, the image is felt to belong only to the family; if it is a ceremony, outsiders', especially Euro-Americans', voyeuristic gaze should be avoided; or that since all historical photography was the result of a colonial process, all photographs represent aggressive acts of the dominant culture on subjugated cultures and are therefore "stolen" images. Despite this growing movement to restrict and remove old images, this author believes we must avoid placing today’s sensitivities on events of yesterday.

As scholars, we cannot right the wrongs of Columbus or take on collective guilt for the actions of our predecessors. What, then, can we do in today's highly charged political atmosphere? In using historical pictures we must give them thorough study, preferably in groups as they were made. This means paying attention to the creators of historical images — the photographers— the subjects of the images, and internal evidence in order to ascertain the original circumstances under which they were made. We must look for internal evidence to determine whether images were made openly or clandestinely. We must look for associated evidence, diaries, letters, newspaper accounts— especially those published at the time the photograph was taken— in order to fairly evaluate the event. As scholars we are responsible for placing these pictures back in their historical context and for insuring that their original message is presented. Photographs are nothing more or less than messages from the past. It is our responsibility to see that viewers today understand an image’s original message, even if that original message is offensive to today's sensibilities.

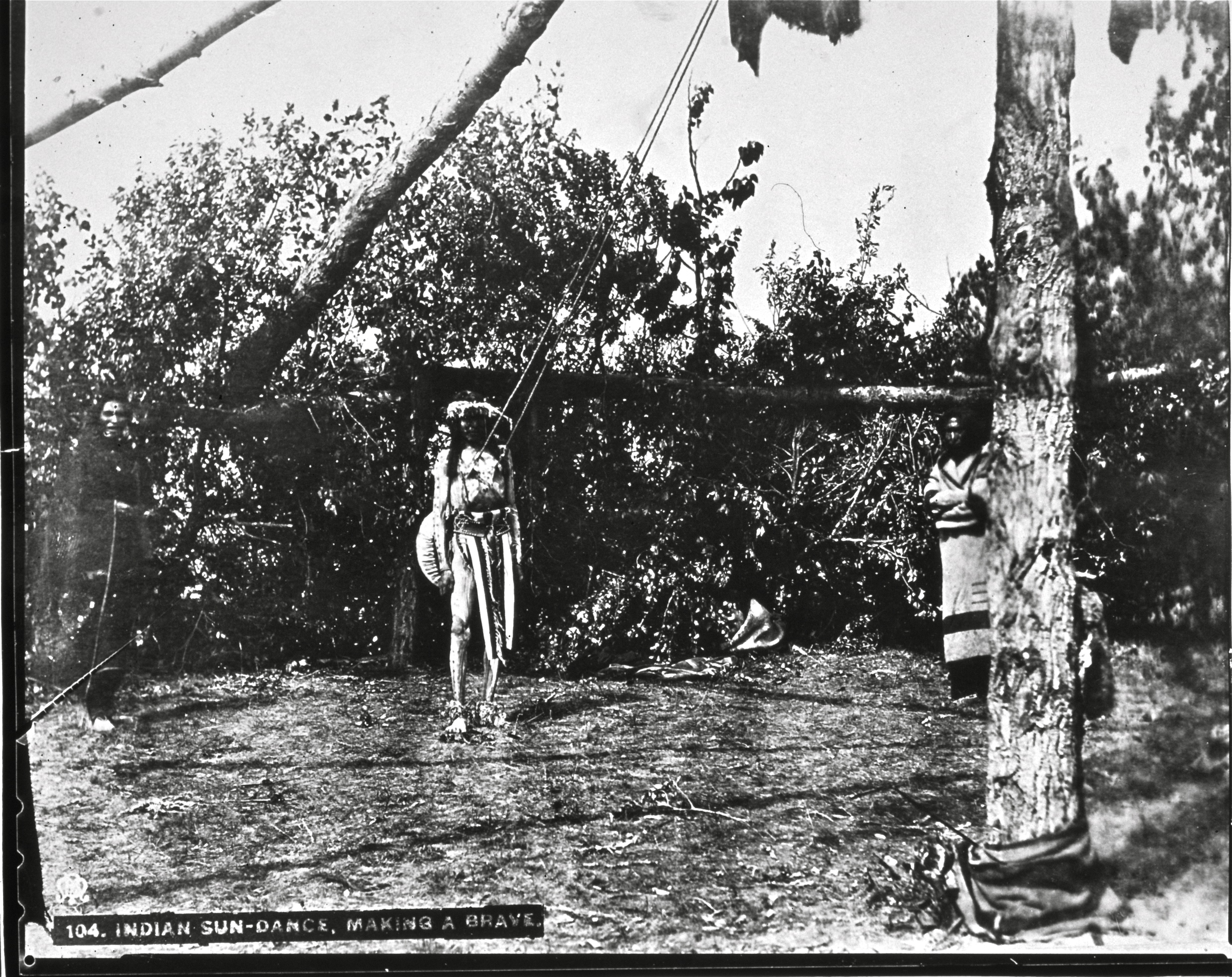

It cannot be denied that Boorne’s photographs taken at the 1887 Medicine Lodge helped to establish self-sacrificial piercing as the icon for the Medicine Lodge/Sun Dance ceremony. Although these photographs have been used out of context, and are viewed differently today than a century ago, there is no justification for their restriction or removal from scholarly scrutiny. Such presentism is not academically sound, although it may be politically correct.

Next Section: Postscript

17 What kinds of photographs are likely to be sensitive and restricted today?

Photographs of human skeletal material associated either with burials (Thomas 1998) or ceremonies associated with mortuary customs such as the drying of a Kwakiutl mummy (Goetzmann 1991: 136) or of deceased Indians such as the frozen dead of Wounded Knee (Fleming and Luskey 1986:63-65).

Photographs of sick or dying individuals (Scherer 1973:141). A drawing by Mary Irwin Wright based on this photograph was reproduced in Stevenson (1894). According to introductory notes by Stevenson (1894:14), this ceremony was totally open to her scrutiny. However, because it was a private, NOT a public ceremony the author would not today publish this image as was done in 1973.

Photographs taken of non-public parts of ceremonies, without the consent of the photographed, such as the backstage of events at a performance. An example of this would be the kachinas at rest with their masks up on their foreheads (Wright, Gaede, Gaede 1986: pl.17). Such non-public photographs would today include images of sweathouse participation (Scherer 1973:75).

Certainly those photographs for which documentation survives that they were taken clandestinely, without permission such as the interiors of Pueblo Indian kivas during or prior to ceremonies. Several examples of photographs exist in the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian and elsewhere of the interiors of kivas. Such photographs were taken probably without permission by George Wharton James at Mishongnovi, showing the loose snakes used in the Snake Dance, and one of the altars with cornmeal design and other sacred paraphernalia used in the Antelope Kiva in a Walpi Snake Dance in 1897-1898.

Where it is clear that photographing sacred items or events caused the participants to fear reprisal from their community. Thus, although Mathilda Stevenson does appear to have had good relations with the Sia and was able to have entrance into many ceremonies there were clearly tensions involved with photographing sacred items. She wrote: "Unfortunately, the flash-light photograph of the altar of the Snake Society made during the ceremonial failed to develop well, and guarding against possible failure, the writer succeeded in having the ho'naaite arrange the altar at another time. The fear of discovery induced such haste that the fetishes which are kept carefully stored away in different houses, were not all brought out on this occasion" (Stevenson 1894:78). Then again when Stevenson was attempting to photograph Zuni religious ceremonies, although the priests and high officials favored the photography, the populace were so opposed that Stevenson felt it prudent to make few ceremonial pictures (cited in Holman 1996b).

Finally, the photographs of individuals in sacred costumes whether part of a ceremony or not. This category of images will undoubtedly keep getting larger and larger as more and more activities or clothing are identified as sacred (see Brumbaugh 1996).